I have an old linux server based on an Abit KN9-SLI motherboard. This is an ancient machine, circa 2006, and it’s seriously creaky; it has only 2GB non-ECC RAM, and that’s not enough.

I want to use it as the host for an RAID-1 array of hard disks where I’ll accumulate all of the files I’ve ever had. Literally. It’s a LOT of data, about 6 TB, but there’s tons of duplication. Dealing with duplicates is another question for later.

First I need a machine with adequate memory to handle the processing I want to do; the existing 2GB of non-ECC isn’t enough. The motherboard takes DD2, and I found cheap 2G unbuffered ECC DIMMs here.

When I put them into the slots on the mobo, it failed to post to the BIOS; it just gave plaintive slow beeps, which indicate RAM trouble. I pulled two DIMMs out, and it did boot. Hmm, maybe the BIOS only knows how to handle 4G? Furthermore, I found that linux wasn’t recognizing the ECC.

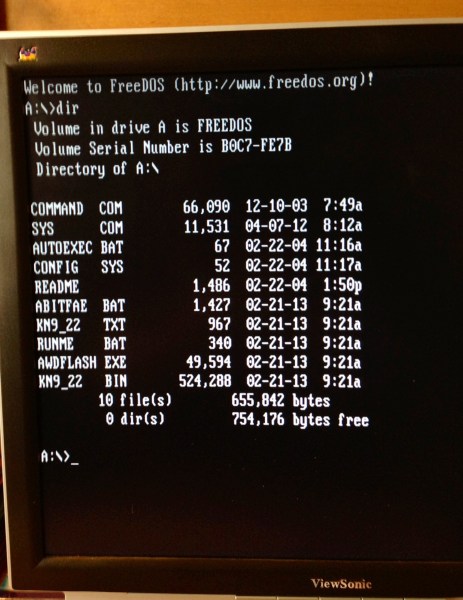

A BIOS update was in order. However, Abit is out of business, and their website has dead links for the actual files. There were links in lots of dodgy places, and I finally found this guy who archived all of Abit’s BIOS updates. Ok, now how to flash it?

The server in question doesn’t have an internal floppy drive, and the CDROM is flaky. I struggled down many blind alleys and wasted a few hours, but finally found excellent instructions on the Ubuntu forums. I created a 1.44M, 3.5″ floppy disk, and booted. Wow, it’s weird to boot into DOS (using an external USB floppy):

I ran the BAT file (my head spins), got a little worried as part of the instructions said that I should check my “floopy” [sic] drive, but I went ahead and flashed the ROM:

Following the instructions in the mobo’s Fine Manual, I reset the CMOS, then added the RAM (so there were all 4 DIMMs = 8G), booted to post, updated all the settings in BIOS, and it worked!

wylbur@snowball:~$ sudo dmidecode # dmidecode 2.11 <snip> BIOS Information Vendor: Phoenix Technologies, LTD Version: 6.00 PG Release Date: 09/04/2007 <---this is the update <snip> Base Board Information Manufacturer: http://www.abit.com.tw/ Product Name: KN9(NF-MCP55 series) Version: 1.x ---dmesg----- [ 6.640164] EDAC MC: Ver: 2.1.0 [ 6.652770] MCE: In-kernel MCE decoding enabled. [ 6.653797] AMD64 EDAC driver v3.4.0 [ 6.653833] EDAC amd64: DRAM ECC enabled. <--- YAY! [ 6.653838] EDAC amd64: K8 revF or later detected (node 0). [ 6.653853] EDAC MC: DCT0 chip selects: [ 6.653855] EDAC amd64: MC: 0: 4096MB 1: 4096MB [ 6.653857] EDAC amd64: MC: 2: 4096MB 3: 4096MB [ 6.653859] EDAC amd64: MC: 4: 0MB 5: 0MB [ 6.653861] EDAC amd64: MC: 6: 0MB 7: 0MB [ 6.653882] EDAC amd64: CS0: Unbuffered DDR2 RAM [ 6.653884] EDAC amd64: CS1: Unbuffered DDR2 RAM [ 6.653885] EDAC amd64: CS2: Unbuffered DDR2 RAM [ 6.653887] EDAC amd64: CS3: Unbuffered DDR2 RAM [ 6.653932] EDAC MC0: Giving out device to 'amd64_edac' 'K8': DEV 0000:00:18.2 ---and here it is----- wylbur@snowball:~$ free total used free shared buffers cached Mem: 8200936 396520 7804416 0 14852 194480 -/+ buffers/cache: 187188 8013748 Swap: 3903788 0 390378

It will run memtest for a day or so, and then back to hammering away at the giant pile of disks. I’ll document that process in a subsequent post.

(Also playing with MarsEdit blog editing software. Current sense: works pretty well, nice clean interface)