It turns out that a 12v/5a battery, when inadvertently shorted through a breadboard, melts 26ga leads in less than a second. And creates very dramatic (if foul smelling) fumes. Good to know.

Here’s the filtration prototype. I’m thinking that we can mount the flow meter to the top of the lower bucket and then create something in the bottom of this bucket to hold the water pump in place.

Here is a video of the evaporator prototype. It is built out of 1/4 ” hardware cloth, a 26″ inverted sled and a ~4′ kiddie pool. It still needs some work on even dispersal of the water. Next we are going to try attaching some burlap to see if that helps get better surface coverage.

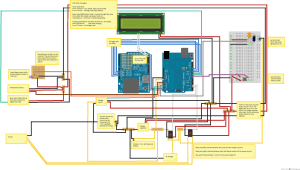

Tonight I did another test of the pump with control and sensing. The flow sensor worked right out of the box. The voltage monitor I made using two resistors and an analog pin took a lot of fine-tuning, but after that it matches my multimeter’s opinion. The water level sensor doesn’t work at all yet, and the water temperature sensor looks like it’s going to be complicated to set up.

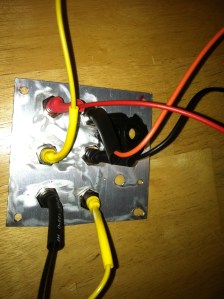

On the data logging shield, the real time clock (RTC) worked immediately, but the SD card gives an ominous message (“Initializing SD card…initialization failed.”). On the Adafruit forums, the main culprit seems to be crappy soldering. Totally likely, so here are photos:

Here’s hoping the ever-helpful Adafruit folks can tell me what I did wrong. PS: in beginning hobbyist electronics, there’s a hell of a lot of value in paying a bit more to get responsive, high-quality customer service, and wow, does Adafruit deliver.

Edit 17 July: yep, crappy soldering. Adafruit support even pointed me to the specific board parts (the digital pin headers) that were probably at fault. Fixed.

While I wait for the various bits of electronics to arrive, I decided to do a slightly more formal test of the pump.

I pumped a pretty much full 5g container up 74″. The pump was sucking air in the reservoir at 2:15, however: there was about 1″ left in the bottom, and the top bucket wasn’t quite full; call it 10/14 * 5g, say 3.6g. I’d say at 74″ of lift, conservatively, this pump does about 1.6 gal/min.

There’s good reason to make sure the pump is fixed standing upright on the bottom of the bucket. That will take a bit of design.

I’ll repeat the test to see if the pump shuts off when it finds no more water, but I’m not sure it does. That’s a bit worrying. All the more reason to have a ton of intelligence (i.e., only let the pump run for 2 min or until there’s 2″ of water in the reservoir. Good thing that the circuit design is well along the way,

The evapotron has a series of challenges. First, I can’t let the charger run while the battery is under load. That will fry the charger pretty quickly. OTOH, lead-acid batteries die when they overstressed or overcharged. This all means means that either I have to constantly check the battery load, or I have to automate it. Also the pump doesn’t seem to know when to quit, in two ways. A) it keeps pumping when there’s nothing more to move; and B) in practical terms, it doesn’t really need to run constantly. It could run every 10 or 15 mins, max.

So if I’m gong to control charging and timing, an Arduino is going to be involved. At that point, I kind of went nuts. Why not keep track of the battery voltage? The pump current? The water level in the reservoir? The water temp? The flow into the reservoir (i.e., total input)? And once all that’s happening, why not log it all to an SD card? And it’s going to need a minimal UI to watch it all. And the next thing I know, I had this.

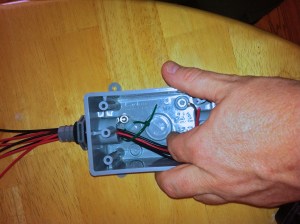

The part on the left is pretty stable. There will be a bunch of wires from the sensors in the reservoir and the pump brought together in a junction box with a 4′ cable to the control box where the Arduino, battery, and charger will live. I’ve just started thinking through how the junction box will work.

The junction box has to be mostly weatherproof (it will be somewhat sheltered under the evapotron) but the control box needs to be sealed. Dust, rain, spilled grey water, etc., need to be kept out. Good thing I bought some Sugru.

I decided to test the 7xF cell NiMH batteries in a realistic way. I charged them fully, attached the Arduino and the LEDs, and I ran a test program adapted from dbu’s LED Globe idea and code. Here’s what the setup looks like:

I expected it to run for about 2 hours, and I hoped for three. Anyway, I put a voltage meter on the power bus, and measured every 15 mins or so. Results in the graph below.

Holy cats. The battery kept 200 LEDs blinking for 477 minutes, nearly 8 hours! So nominal 8.4v batteries supplying 13 Ah are more than enough. The power curve is nice and flat until it fails, which is excellent.

Holy cats. The battery kept 200 LEDs blinking for 477 minutes, nearly 8 hours! So nominal 8.4v batteries supplying 13 Ah are more than enough. The power curve is nice and flat until it fails, which is excellent.

A couple of observations here. First, the Polulu voltage regulators totally rock, hella efficient. At no point were they even slightly warm to the touch, so nothing wasted as heat. Second, in real use, the LEDs draw way, way less than their rated max current. Third, the giant, ridiculously heavy batteries are more than enough. No Li-Ion polymer for me, at least in this round.

I’ve mentioned before that I’m building an Evapotron, a device for making grey water (i.e., water used for washing dishes and people) evaporate so it doesn’t have to be packed out.

Today I tested a mechanism for driving grey water up and over the pumped cascade which is the model for this implementation. In short, I need to get dirty water out of a reservoir, lift it about 6′, and let it dribble over a snow saucer and thence down a cylinder to be exposed to sun and wind. A friend suggested that a submersible bilge pump would be a good choice.

I got a couple of Rule 25s automatic pumps. These guys have an internal circuit to check every 150 seconds if there’s water present. If so, they run ’til they suck dry, then go back to waiting. That’s perfect for this application. I’ll power them with a cheap 12v lead-acid battery. In the first test, it works.

The battery will live in a sealed (against dust and water) clear plastic box next to the bucket where the pump sits. Inside the box will be the battery and a charger. The charger will connect to the (highly flaky) camp AC. The charger is “smart” in the sense that it knows only to charge when the battery’s voltage is low. Still, I’d like it to turn off periodically, and I’d like to turn the pump off at about 7pm through about 8am in the morning. I’m thinking of building a real time clock + Arduino that could control the charger via a PowerSwitch tail and the pump via a relay.

I can think of many other uses for such a circuit. For example, it would be nice to turn on a power strip that charges all my rechargables one night per month (they usually sit dormant for months and die). It might also send me email about the status of the batteries.

Anyway, my project partner P has a bunch of good ideas for the actual mechanism of the Evapotron. I think this is going to be excellent.

I’m hardly an expert in anything, but I’ve accumulated a few ideas and a little experience as I’ve gotten cranked up in the last couple of months. I put together this list of resources and stuff for starting in Arduino hacking.

The first thing you need is a bunch of tools, and Lady Ada’s toolkit helped me. One tool that was missing but has drastically improved my work is a self-adjusting wire stripper. You’ll need an Arduino, of course, and a nice kit with a few supplies is a good start. You’ll need an intro to the programming language (Wiring), and this book is a gentle intro. This book from O’Reilly is a more advanced programming book but with more useful stuff to do. For all the deep reference material needed for any programming language, see the Arduino site itself.

If this page helps you,

It’s a standard hack: take an old computer’s power supply and turn it into a clean source of DC power for electronics hobby-izing. There are great youtube videos, wikiversity articles, instructables, and blogs about how to do it. One more can’t hurt, but I’m not going to talk about which wire goes where or what resistors to use. There’s already plenty about that on teh interwebz.

The point is to save money, I think. ATX power supplies are essentially free as people dump desktop machines in favor of newer desktops (rare) or laptops (nearly everyone). So go harvest. But for me, the bigger point was to practice project planning, doing soldering, integrating components. In pursuit of the blinky coat, I don’t feel that my skillz are there yet.

Earlier this week I tried the first time. In short, I forgot the “lay out the interface first” rule. Power supplies are generally built on a chassis with a second piece of metal that slides on as a cover. On most power supplies, the chassis pieces extend on two sides, holding the fan and AC input on one side and a lot of mesh for airflow on the other. No problem, I though, I’ll put the binding posts on the cover. Very, very bad idea.

I got the thing working, briefly, but there were a lot of shorts. Here are the lessons I took away:

- Everything fixed must go on the chassis so the top can be moved aside. Don’t complicate opening the box by wiring stuff to the top pieces.

- Make sure everything you plan to solder can be pulled out and worked on in the open. This is a planning step.

So the first attempt failed. The wiring got in the way of the box closing. Although the power on the binding posts looks good, I figured that catching fire was a likely outcome. I ditched it and harvested another power supply.

This time I took a lot more time figuring out how I’d lay out the binding posts, LEDs, and switch. I pulled the fan out and moved it to the front of the box to make room.

Then I cut away the grill where the fan used to be. Turns out that the aluminum sheet is so soft I could cut it with wire snips.

Using a Dremel, I cut an aluminum plate from an enclosure I had. This is the plate on which the binding posts, LEDs, and switch will be mounted.

One of the several failure modes I had in the first try was trying to solder a dozen-odd wires to the binding posts in place. Not only was I wrapping a giant mess around a tiny post, I was doing so underneath and behind piles of other wires. Most of the online instructions to do this mod skip this part, saying breezily “connect all the yellow wires to the yellow (12v) post.” Uh, how do you connect that many wires to a single post? I decided to simplify by cutting each wire bundle as short as possible. Later I’ll wire-nut them together with a single strand that runs to the binding post.

Next I drilled holes in the plate and mounted the binding posts on it. Wow, am I a crappy craftsperson. I couldn’t get the holes to line up neatly, alas. For the holes for the two LEDs, I got the holes slightly too large (I was using a multibit, which is tough to feel as you drill through soft aluminum). Some liquid electrical tape secured the LED holder outer ring in place.

Next I set up a circuit for the LEDs. They each need to share a ground with the switch (which I figured out how to solder from this video), then a resistor (330 ohm), before connecting to the LED negative side. I wired the resistors inline, and connected all the grounds via a pigtail. Note to self: with heat shrink, less is more. Cover the solder, but don’t go crazy, it just makes the wires stiff and hard to work with.

You can see the resistors peeking out from under the shrinkwrap. They’re there to prevent the LEDs from frying (they want approx 3.3v but they’re getting 5v). Hot glue fixed the LEDs into the holders.

ATX power supplies need a load or they won’t turn on, and the standard hack is to put a 10 ohm/10w resistor between a 5v (red) line and ground. I did it inline, and hot-glued it to the chassis wall.

Finally I bolted the panel on and ran all the wires from the panel to the pigtail bundles. For each bundle, I zip-tied the bundle with the wire from the panel, twisted them together, soldered them, screwed a wire nut on top, then put a couple of turns of electrical tape. The wire nut obscures the zipties, but they’re key to keeping order.

Turned it on, and it works! No burning smell 🙂 even after an hour of driving 13A of blinkies.

Yay! This will be very useful as the blinkies go into advanced testing. It was also a good lesson in project planning and assembly skills, which was the point, after all. And doing it, I wonder if I need a better soldering iron. I’m seriously in a tool orgy in the last couple of months, and it does feel good.

Yay! This will be very useful as the blinkies go into advanced testing. It was also a good lesson in project planning and assembly skills, which was the point, after all. And doing it, I wonder if I need a better soldering iron. I’m seriously in a tool orgy in the last couple of months, and it does feel good.